April 12, 2025

The Breakdown

“Extinction is nature’s way of editing.”

Some species are gone because we erased them. Others are gone because natural selection said it was time.

Bringing back extinct species due to human activity could be a path to redemption. Bringing back extinct species under any other circumstance could be a violation of nature itself.

Natural selection doesnt ask for permission – and it doesn’t make mistakes.

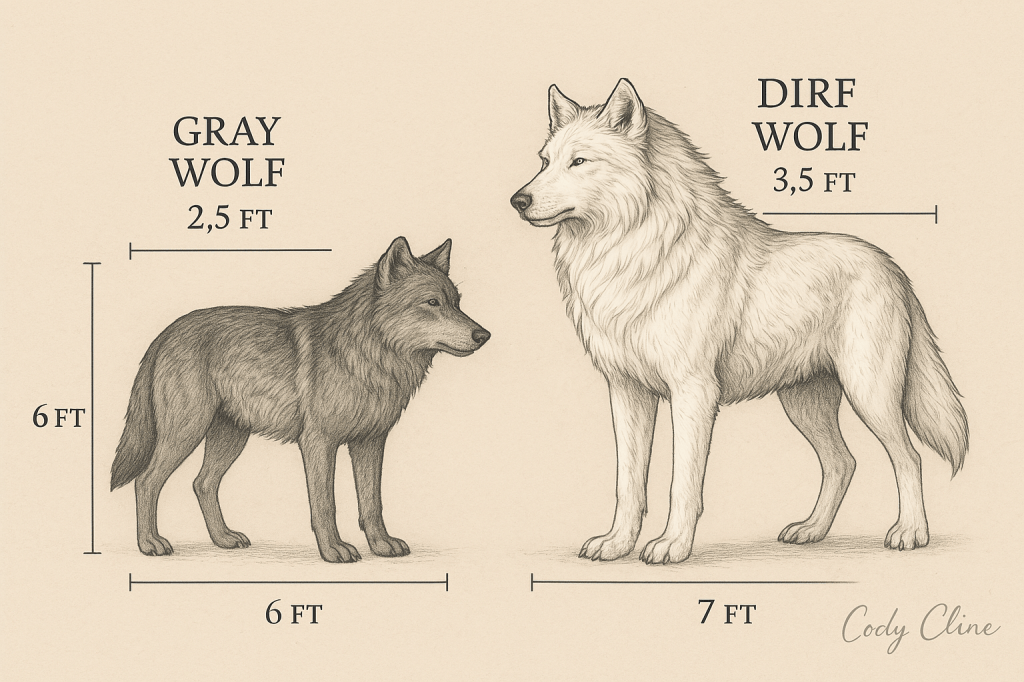

In 2021, scientists dropped a bombshell: dire wolves, long believed to be close cousins of gray wolves, were something else entirely.Their DNA revealed a separate lineage, diverging from other canids nearly six million years ago (Perri et al. 87). Canids are mammals that belong to the biological family Canidae, which includes dogs, wolves, foxes, jackals, coyotes, and other dog-like carnivores. They weren’t just big wolves – they were strangers. This revelation sent ripples through the world of genetics and conservation.

The news of the dire wolf’s deep genetic divide sparked a larger, more pressing question: Is it ethical to bring back animals from extinction? If we have the tools to do it, does it mean we should?

The short answer? Sometimes. But not always.

Undoing Our Own Damage

When humans are the reason a species disappears, I believe we have a moral obligation to try and bring it back – if not for the species itself, then for the ecosystems we disrupted. Like the Passenger Pigeon, the thylacine, and the Steller’s sea cow didn’t disappear because they couldn’t survive. They vanished because we overhunted, bulldozed habitats, and introduced invasive species faster than they could adapt.

Reviving these animals, when done responsibly, is a chance to undo some of the damage. As ethicists Jacob Sherkow and Henry Greely argue, “if we are responsible for the extinction of a species, we may also be responsible for its restoration” (Sherkow and Greely 353). These species were part of a relatively modern ecosystem – one we’re still living in – and their return could help restore lost balance.

But that’s not the full picture.

When Extinction Is Nature’s Decision

Natural extinction – the slow; often brutal result of changing environments, evolutionary pressure, or genetic limits – is different. That’s not a mistake to fix. Thats nature’s call.

Reviving animals that disappeared thousands or millions of years ago violates the most basic principle of evolution: natural selection. Natural selection is the process by which species evolve over time based on their ability to survive and reproduce in a changing environment. In simple terms, the traits that help an animal thrive are passed down, while the traits that don’t – and the creatures that carry them – slowly disappear. It’s nature’s way of editing life, favoring what works and quietly removing what doesn’t. These species didn’t just disappear – they failed to adapt. Their time ended because they no longer fit the environment. Bringing them back doesn’t restore anything. It rewrites the rules.

Take the dire wolf. It once thrived in the Pleistocene epoch, hunting large Ice Age megafauna like bison, sloths, camels, and even juvenile mammoths (Perri et al. 88). It was massive, muscular, and built to bring down big prey in packs. But those prey species are long gone. And in today’s environment, where smaller, faster animals dominate – like deer and rabbits – the wolf’s powerful build would be a liability, not an asset.

That’s why we have gray wolves – sleeker, more agile, and better adapted to hunt the animals that remain. They evolved to thrive in a world that has changed. The dire wolf didn’t – and that’s why it’s gone.

Bringing it back now wouldn’t be ecological restoration. It would be an unnatural insertion into an ecosystem that evolved without it. And evolution is not just biology – it’s balance. It’s nature saying this works now. That doesn’t anymore.

Natural selection exists for a reason. It’s the final word in the species story. When we override that with modern technology, we’re not saving nature – we’re bending it to our will. As philosopher Christopher Preston writes, “when humans decide which species live and die, they move from being participants in nature to engineers of it” (Preston 214). And engineers don’t always know the consequences of what they build.

It’s not just irresponsible – it’s unethical.

The Illusion of Control

De-extinction might sound noble, but if it becomes about curiosity, profit, or prestige, we risk losing sight of its purpose. Are we doing this to restore balance? Or are we doing it to prove we can?

Bringing back an animal just because it is cool, ancient, or iconic is a shallow reason to mess with millions of years of evolution. Dire wolves weren’t what we thought – and many species we fantasize about resurrecting probably aren’t either. The world they once knew is gone. When you revive what nature has already erased, we’re not healing the planet – we’re rewriting a story that was never ours to finish.

Resurrection or Responsibility?

De-extinction isn’t inherently wrong. But it isn’t inherently right, either. If we’re going to bring species back, it has to be for the right reasons – and the right species.

When humans caused the damage, restoration makes sense. When nature made the call, resurrection becomes violation.

Just because we can, doesn’t mean we should.

Works Cited

Perri, Angela R., et al. “Dire Wolves Were the Last of an Ancient New World Canid Lineage.” Nature, vol. 591, no. 7849, 2021, pp. 87-91. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-03082-x.

Preston, Christopher. The Synthetic Age: Outdesigning Evolution, Resurrecting Species, and Reengineering Our World. MIT Press, 2018.

Sherkow, Jacob S., and Henry T. Greely. “De-Extinction.” Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, vol. 14, no. 1, 2013, pp. 347-67. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153538.

Leave a comment